The Myanmar junta’s execution of four political prisoners less than a week before a major gathering of foreign ministers from the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) has served as a sobering reminder of how little influence the regional grouping has over its most recalcitrant member.

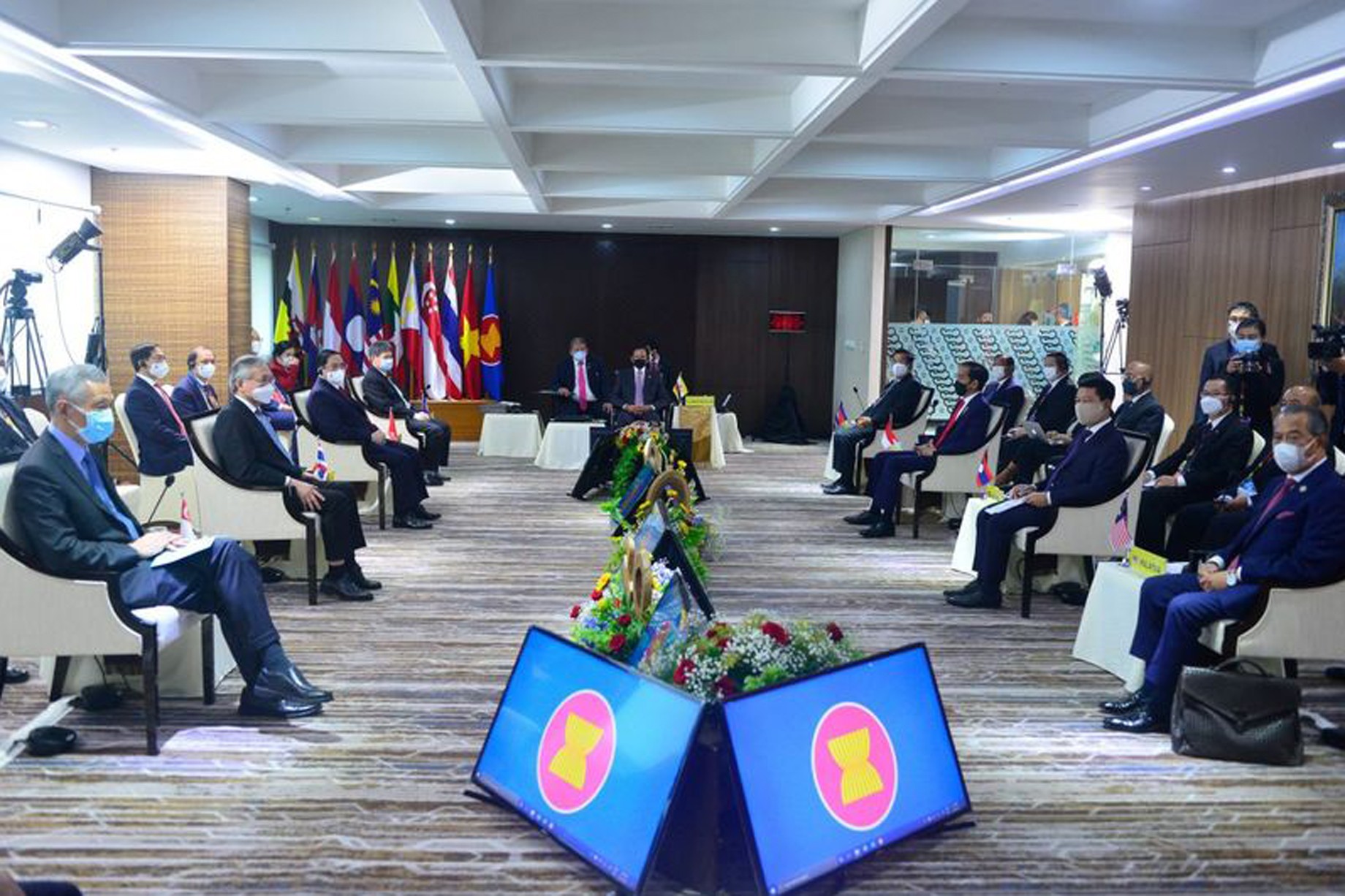

Despite ostensibly playing a key role in efforts to end the ongoing crisis in Myanmar, chiefly through its so-called “five-point consensus” reached in April of last year, ASEAN has yet to have much impact in its efforts to end the country’s spiral of violence. Indeed, last weekend’s executions have put the world on notice that worse may be yet to come, as the junta struggles to gain control over a situation of its own creation.

Indeed, the timing of the regime’s latest outrage suggests that Min Aung Hlaing, the leader of the coup regime, is sending a clear message: that he will do as he sees fit to crush opposition to his rule—five-point consensus be damned.

But as Myanmar’s political crisis moves steadily closer to becoming a full-blown human catastrophe, ASEAN continues to act as if it can still be managed somehow through the usual means, including backdoor diplomacy and public calls for “restraint” from all sides. Meanwhile, the United Nations and the international community watch from the sidelines.

This approach, which has so far achieved nothing in the way of progress, only gives the junta more time to cement its hold on power, while prolonging the suffering of ordinary people. It is time, then, for ASEAN to take more meaningful action.

Perhaps the most important first step that the bloc and its members can take is to acknowledge what is at stake. It must, in other words, stop seeing this as just another embarrassing episode that its perennial problem child has dragged it into and deal with it as a regional emergency of the first order.

That was the very clear message sent by Mitch McConnell, the US Senate minority leader, in his recent statement in response to last week’s executions. “It is time for ASEAN states to step up, individually and collectively,” he said. “As the junta plunges Burma deeper into chaos and civil war, the turmoil will affect the entire region.”

Warning that Myanmar could end up as “a failed state wracked by civil war like Syria” or “a Russian or Chinese-backed client state,” McConnell urged the country’s neighbours to impose real costs on the junta for its egregious acts of terror towards Myanmar’s people.

There are a number of reasons that ASEAN has refused to take a stronger stance in the past. One is its policy of non-interference in the “internal affairs” of its members; another is a sense of solidarity in the face of outside pressure. But now there may be one more: the very real possibility that the junta will quit the grouping rather than submit to its demands.

There have, in fact, been rumours that Min Aung Hlaing is indeed considering this move. If true, that might dampen what little enthusiasm there is among ASEAN’s members for tougher action. Nobody wants to be responsible for the bloc’s disintegration.

But if unity comes at the cost of jettisoning every other principle that ASEAN professes to stand for—including rule of law, good governance, and respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms—it may not be worth the price.

There is, however, an alternative to giving in to blackmail. It can be argued, in fact, that as the leader of an illegitimate regime, Min Aung Hlaing does not have the authority to take Myanmar out of ASEAN. That authority rests solely with the democratically elected civilian government that he ousted in February 2021.

The option that ASEAN has, then, is to recognise and communicate with the National Unity Government (NUG), which was legally established on the basis of the results of the 2020 election. So far, this is something that only one ASEAN member, Malaysia, has done.

By accepting the NUG as the rightful representative of Myanmar, ASEAN would not only remove the threat of the country leaving the fold, but also demonstrate a stronger commitment to its own core principles, as enshrined in the ASEAN Charter.

At the same time, it would strengthen the hand of the NUG by further eroding the junta’s claims to legitimacy and making it easier for it to work together with the United Nations and other countries to re-establish civilian rule in Myanmar.

As long as Min Aung Hlaing’s regime believes that it will ultimately prevail in its efforts to erase the NUG and the forces that support it, it will continue to push Myanmar closer and closer to the brink of collapse. Only when it knows that it cannot achieve this objective will it pause in its killing and look for another way out of this self-inflicted disaster.

For ASEAN to fulfil its role as a force for stability in the region, it must sometimes be prepared to make bold moves. In Myanmar, brute force has been allowed to rule for too long, resulting in a power imbalance that must be redressed. It is up to ASEAN, then, to restore that balance so that the country, and the region, can move forward in these difficult times.