Noor Kamal, 31, was one of more than 700,000 ethnic Rohingya from northern Rakhine State who marked the fifth anniversary of their painful exodus from their homeland this past August. Now living at the Shofiullah Kata refugee camp in Bangladesh, Noor can hardly imagine what his native village of Myin Hlut, in conflict-torn Maungdaw Township, looks like now.

There was once a large market at the centre of this prosperous village of some 20,000 inhabitants that Noor remembers as his favourite place to be when he was growing up. Now a father with a four-year-old son and a two-year-old daughter, his own parents had three acres of land in Myin Hlut that they farmed to provide for their children. When he and his family were forced to flee in 2017, Noor was running a pharmacy in the village.

Since then, the entire village has been razed to the ground—burned and bulldozed by the military forces that emptied it of its Rohingya residents. Most of the land where the village once stood is now occupied by border guard forces under the command of the junta that seized power in February 2021.

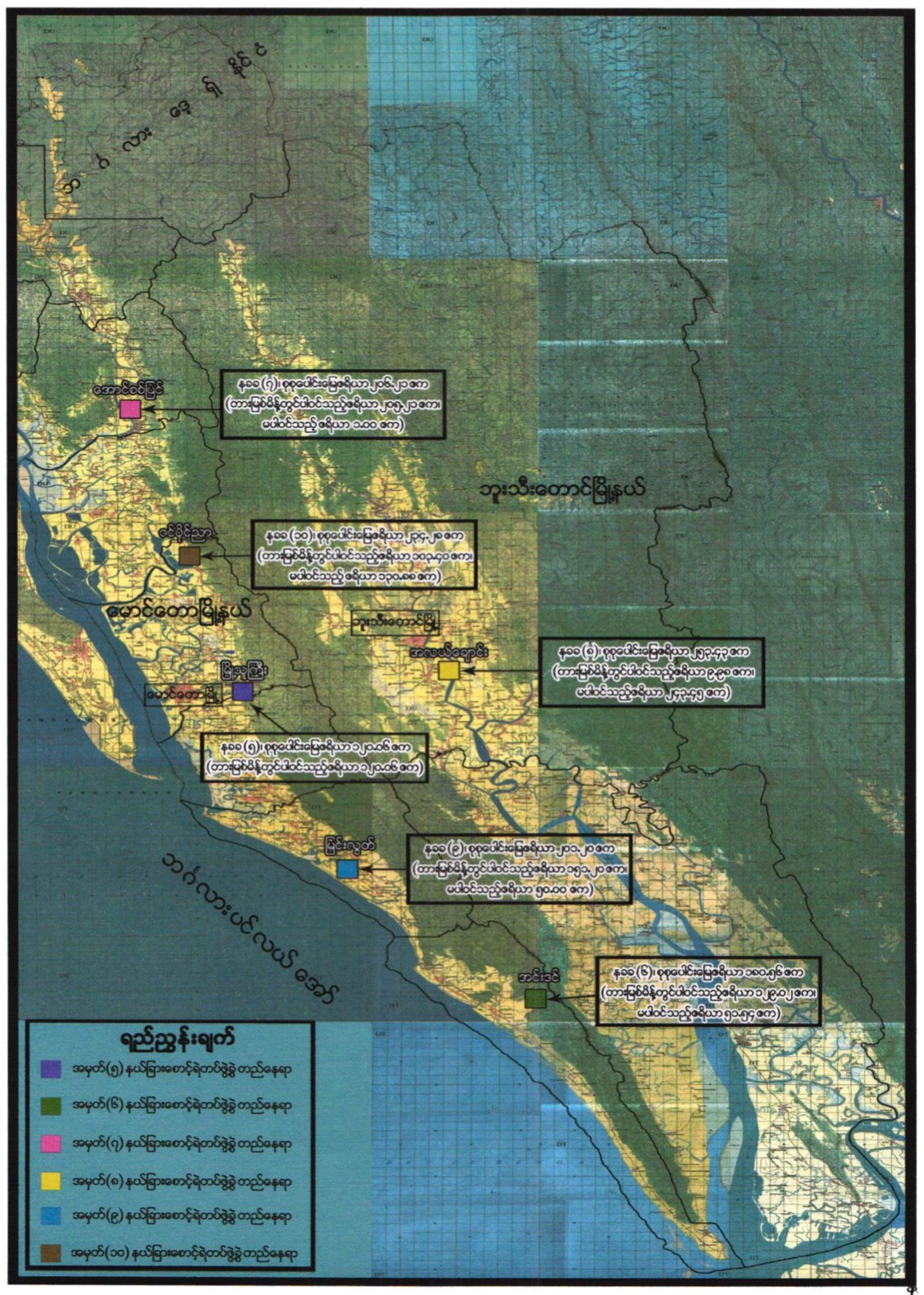

Now, five years after taking this land from those who had lived there for generations, the regime is preparing to officially transfer ownership to its current occupiers, according to documents seen by Myanmar Now. A total of more than 700 acres in two townships—Maungdaw and Buthidaung—are about to be handed over to the military-controlled No. 1 Border Guard Police Division Office, the documents show.

Reversing an NLD directive

In September, the regime’s deputy minister of home affairs, Maj-Gen Soe Tint Naing, sent a letter to Zaw Than Thin, the permanent secretary of the Ministry of Union Government Office, requesting permission to repeal a “regional directive” issued by Maungdaw’s General Administration Department (GAD) two years ago restricting the use of lands abandoned by “Bengalis”–the term used by Myanmar authorities to deny the ethnic identity of the Rohingya. He said in the letter that the purpose of the repeal was to “officially register the ownership of those lands under the No.1 Border Guard Police Division Office.”

In response to the request from the Home Affairs Ministry—which manages Myanmar’s border guard forces—Zaw Than Thin ordered the junta’s Rakhine State Administration on October 8 to proceed with the repeal.

Although this move did not come as a surprise, it is significant because it marked the official cancellation of a belated effort by Myanmar’s ousted civilian administration to prevent the illegal occupation of land belonging to Rohingya forced to flee military “clearance operations” in 2017. On February 15, 2020, the Maungdaw Township GAD was instructed by the then National League for Democracy (NLD) government to issue a directive barring “individuals not associated with [the affected land] from living, growing crops, and farming there.” That directive was signed by Zaw Than Thin, who was also permanent secretary of the Ministry of Union Government Office under the NLD.

When he spoke to Myanmar Now by phone in mid-October, Noor was not aware of the junta’s plan. However, he knew that it was unlikely he would ever be allowed to return to his birthplace or reclaim his family’s land under the current regime.

“We have been persecuted and discriminated against like this for a very long time. There is nothing we can do if they decide to confiscate our land,” he said.

While land confiscation by the military has long been a problem faced by ordinary citizens all over the country, the Rohingya have always been especially vulnerable to this practice due to their lack of official recognition by successive military regimes.

In the 1990s, the Rohingya were subjected to ever-worsening persecution by the Maungdaw-based Border Immigration Headquarters—better known by its Burmese acronym, Na Sa Ka—which enforced restrictions that extended from their freedom of movement to their right to marry and have children. Land and other property was also taken from thousands of Rohingya and used to create “model villages” for settlers from central Myanmar or ethnic Rakhine and other predominantly Buddhist minorities.

According to Nay San Lwin, the co-founder of the activist group the Free Rohingya Coalition, the latest move by the regime means that even if Rohingya genocide survivors are ever allowed to return to Myanmar, they will be forced to live in concentration camps, like those created for displaced Rohingya villagers in Sittwe, the state capital.

“All these lands must be returned to their Rohingya owners once a democratic government is back in power,” he told Myanmar Now.

A vacuum left by violence

Noor and his four sisters grew up in a wooden house in Myin Hlut, which is located about 25km southeast of the town of Maungdaw. He graduated from high school in 2012, but wasn’t able to continue his studies in Sittwe, because of the outbreak of violent clashes that year between the Rohingya and the majority Rakhine people. So he stayed in Myin Hlut, where he worked as a tutor for primary and middle school students while running a pharmacy.

At the time, he hoped that the tensions would soon blow over. However, when a second wave of violence—this time carried out by the military—struck five years later, he and the other residents of Myin Hlut were all completely swept away by it, leaving a vacuum that the military was quick to fill.

According to the documents seen by Myanmar Now, the junta’s No. 9 Border Guard Force currently occupies more than 200 acres of Myin Hlut, including more than 150 designated as restricted land covered by the NLD directive.

“Those were lands owned by us since the time of our ancestors. They built houses and villages, grew crops, and paid taxes,” said a former Myin Hlut village administrator who is now living in the Balukhali refugee camp in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh. A fire destroyed much of the camp in March of last year and also left more than a dozen Rohingya refugees dead.

For Mohammed Rezuwan Khan, 25, the confiscation of his family’s land is just the latest of many injustices that Myanmar’s military has committed against the country’s Rohingya community.

“I feel very sad hearing this news. The military confiscating our lands like this is very unfair,” he said from the Kutupalong refugee camp in Cox’s Bazar, where he now lives.

Before fleeing to Bangladesh, Mohammed owned 15 acres of land in Inn Din, a village that made international headlines when a Reuters investigation exposed the military’s murder of 10 locals there in 2017. For their coverage of this notorious incident, two local reporters for the London-based news agency were arrested and sentenced to prison. Among the victims were two young men that Mohammed had taught English to when he still lived there.

Where Inn Din once stood, there are now border guard outposts that occupy more than 180 acres of land, including 129 acres designated as belonging to Rohingya residents.

Getting rid of the evidence

Nay Myo Thet, a 32-year-old army captain who deserted his post in Buthidaung Township earlier this year to join the Civil Disobedience Movement, witnessed first-hand the military’s efforts to erase the Rohingya from northern Rakhine State.

Now living in India with his wife and five-year-old child, he told Myanmar Now in an interview shortly after his defection that an engineering battalion was sent to the area when he was there to remove not only the charred houses that had been torched by soldiers, but also the remains of those who had lived in them.

“They bulldozed the land to get rid of the evidence,” he said. “By evidence, I mean the dead bodies and what was left of the houses that had been burned down.”

Nay Myo Thet said he spent more than half of his 13 years in the military in Rakhine State, where his battalion was deployed to take part in a mission to “clear” a stretch of land along Myanmar’s western border by destroying a string of Rohingya villages in Maungdaw Township.

“The military columns would raid and torch villages and burn them to ashes. It all happened before my own eyes,” he said of the mission, which began in 2016 and continued until August of the following year.

Nay Myo Thet said he also witnessed the aftermath of another notorious incident in the village of Gutarpyin, where an Associated Press investigation uncovered Rohingya bodies buried in mass graves. Some of the bodies had acid poured over them, according to the AP report.

A subsequent court martial held to try those responsible for the massacre was merely a “performance” to hide the military’s crimes, he said.

‘They want the Rohingya gone’

Under the junta’s arrangement, the border guard outposts that the army built at that time will soon take official possession of the Rohingya community’s lands. In addition the land in Myin Hlut, this includes 120.06 acres in Myo Thu Gyi (Yar Zar Bi), 205.21 acres in Aung Sit Pyin, 103.40 acres in Zin Paing Nyar, and 9.98 acres in Ah Lel Chaung.

According to Nay Myo Thet, this move effectively settles the matter for the military, which has no interest in accepting responsibility for its treatment of the Rohingya, which it considers entirely justified.

“The military as a whole thinks that the Rohingya are the source of all the problems,” he said. “They just want the Rohingya people gone. That’s all they want.”

The former Myin Hlut village administrator who is now forced to live in theBalukhali refugee camp in Bangladesh agreed that the regime is intent on “erasing” the Rohingya community once and for all.

“By uprooting our lives, they are trying to erase our people, our ownership and our community,” he said.

For Noor, however, his home will always be the village on Myanmar soil where he grew up, even if it has been ploughed into the ground like so many others in northern Rakhine.

“Even if we are living in a Bangladesh refugee camp, our souls are in Myanmar. We are like prisoners here. When can we return to our homes?”

***