The junta’s announcement that a group of people have been sentenced to death is part of an attempt to instill fear in Myanamr’s population, legal experts have said.

Military-run television last week announced that 19 people from Yangon’s North Okkalapa township, which is under martial law, had received the sentence for killing an army officer’s associate, beating the officer and stealing their guns in late March.

Only two of the 19 – Aung Aung Htet and Bo Bo Thu – have been captured while the remaining 17 were convicted in absentia.

“They’re announcing death sentences but they’ve been killing people recklessly on the ground,” said a lawyer who has been providing free legal aid to protesters and wished to remain anonymous. “They’re officializing fear.”

On Tuesday night, seven people who were accused of killing a woman in Hlaing Tharyar on March 15 were also given death sentences by a military tribunal, according to state-run newspaper The Mirror. Four have been arrested and three are still on the run, the paper said. Hlaing Tharyar is also under martial law.

The death penalty has been officially on the books in Myanmar since 1988, but authorities have never carried out an execution, said lawyer Kyi Myint.

He believes, contrary to concerns raised by some rights groups, that the military will maintain this moratorium on executions. “They’re just scaring people. They gave the death penalty but they won’t go through with it. So many were given the death penalty during the Than Shwe regime. But no one was executed,” he said.

Myo Aung, a lawyer in Myawaddy, Karen State, said: “They mainly want people to fear them. They want people to be scared of them and bow to them. If people show their loyalty to them and listen to what they say, they will immediately be safe from being murdered by them.”

In a civilian court, the death penalty is given by a district level court and must be appealed within seven days. Appeals can be made at state and regional courts, the Supreme Court, and to the President. Only if the President rejects the appeal is the sentence final.

Since the coup, appeals must be made to the military council or the head of Yangon Regional Command.

“The law is a weapon to stabilize the administrative mechanism,” he said. “This case carries that principle. I assume it depends on the idea that people won’t dare to do the same after this precedent.”

The junta’s armed forces murdered at least 10 people in North Okkalapa on March 3 and injured dozens of others, according to a volunteer group based in the township.

Protesters said there could have been over 20 deaths that day, but Myanmar Now has not been able to confirm that number.

Over 100 young protestors were arrested in the township on the morning of March 10 when armed forces broke up a protest near Kan Thar Yar park.

On March 14 and 15 the military council declared martial law in Hlaing Tharyar, Shwe Pyi Thar, South Dagon, North Dagon, Dagon Seikkan, and North Okkalapa townships.

It also announced 23 crimes that would be heard by the military tribunal if committed under areas covered by martial law.

The 19 who were sentenced to death are accused of murdering Thant Sin Htwe, who was accompanying Captain Htet Aung Kyaw.

The junta said the killing took place at 3:30pm on March 27, but locals said it must have actually happened in the early hours of the morning that day, while the curfew was in effect, because the arrests began at 8am.

Military trucks took over the local ward administration office at 6am and started arresting people on Aya Kyaung street and several other streets two hours later, a witness told Myanmar Now.

“They captured everyone they could find,” the witness said.

Family members said that Aung Aung Htet and Bo Bo Thu were arrested and taken from their homes at 11:30am.

“They were beating up boys on Aya Kyaung street and asking who they had seen going out for protests and all that,” said Bo Bo Thu’s mother, Aye Aye Thin.

“When they came to Bo Bo Thu, they had this boy named Aung Htet in handcuffs who was beaten up badly. And he was saying ‘This is it, this is Bo Bo Thu’s house,’” she said.

Bo Bo Thu, who was eating a meal at the time, got up to run but the soldiers caught him and took him away after beating him up, Aye Aye Thin said.

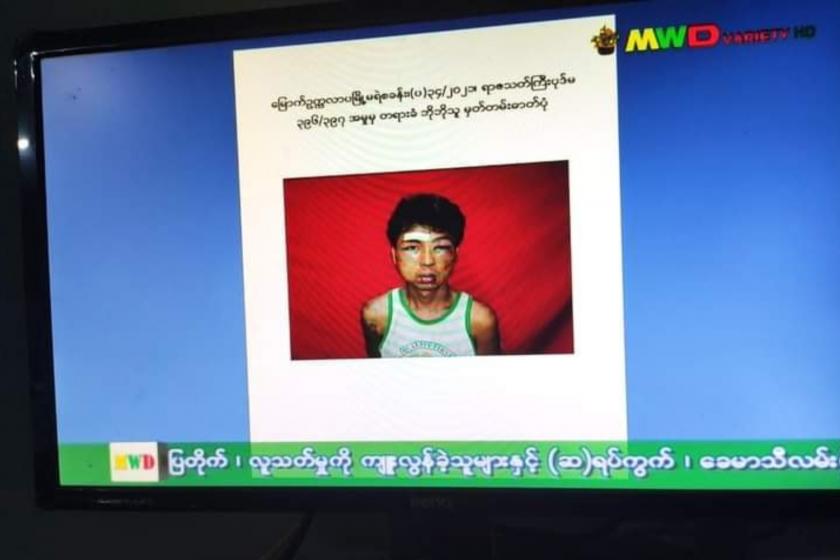

Later, she saw her son, who is 28, on television covered in bruises. “He was bleeding; I couldn’t even recognize my own son… I only recognized him because of the shirt,” she said.

Aung Aung Htet, 27, was arrested while recovering from surgery for an injured leg. He suffers from other health issues and was unable to work, said his mother Myint Myint Than.

“They took him for what happened the night before,” added, referring to the killing. “They said an older person should come along, so his dad went. They took him to the Nya ward administration office. There were others who had been arrested as well.”

A lawyer working pro bono will make an appeal in his case through the prison management department, she added.

Over 40 people were detained and interrogated that day at the administration office until 8pm, and about twenty were then taken somewhere else, a witness said.

The military council has announced that appeals can be requested to the chair of the council and the Yangon Region Command Commander, and only the two of them have the right to make changes to cases or dismiss them.