Since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine on February 24, Myanmar’s people have been following the situation with great interest. This interest is mixed, however, with a certain amount of chagrin. While most have expressed solidarity with the Ukrainian people, many have also wondered why their own country’s struggle with an oppressive regime has not attracted anything near the same level of attention from the West.

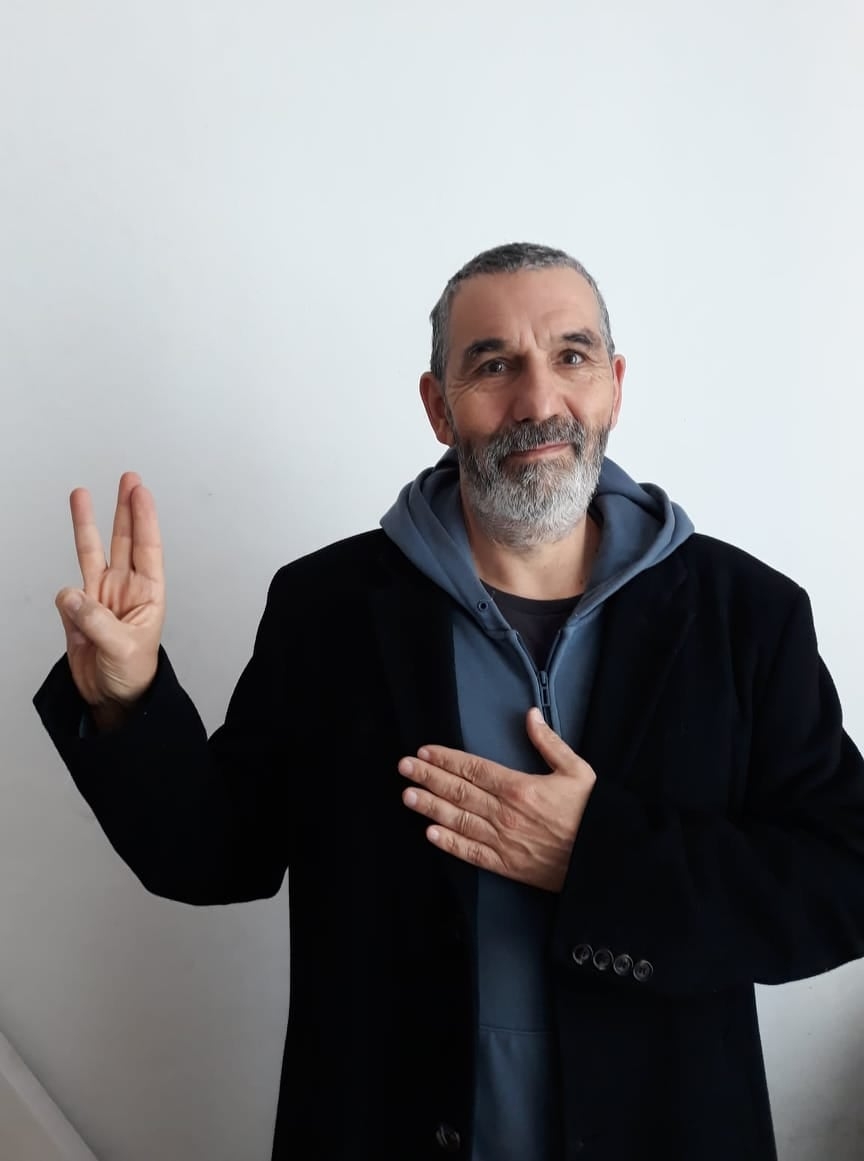

To put the situations in the two countries into perspective, Myanmar Now recently interviewed Igor Blazevic, a prominent human rights campaigner based in the Czech Republic. A senior adviser with the Prague Civil Society Centre, he has also been the director of Educational Initiatives, a training program for Myanmar activists based in Thailand.

In this interview, he discusses the similarities and differences between the Ukrainian people’s defensive war against Russian aggression and the anti-regime resistance movement in Myanmar. He also shares his thoughts about what Myanmar’s shadow National Unity Government (NUG) can do to more effectively lead the struggle against military rule.

The international response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has been very strong. Foreign governments have imposed stiff sanctions and even sent weapons to support Ukrainian forces. In Myanmar’s case, there have been some sanctions, but there hasn’t been any military support. Is this something the NUG should be seeking?

It is understandable that citizens of Myanmar are following developments in Ukraine with great interest. In both cases, we have an archetypal David-and-Goliath struggle—a struggle of civilians, of the whole nation, against a murderous and criminal regime.

However, it would be wrong to make hasty conclusions and draw false parallels. The current war in Ukraine is changing global geopolitics and will have, in the course of time, a significant impact on international politics. But the impact on Myanmar will not be straightforward and will take time to materialise.

It is true that the US, UK and European Union member states have reacted much more strongly, much more quickly, and much more resolutely in response to Russian aggression against Ukraine than Putin expected. However, we should not forget that the US, UK and EU reacted in a very weak way when Putin militarily intervened in Georgia in 2008 and when he annexed Crimea and sent his “green men” to instigate separatist movements in Donetsk and Luhansk in East Ukraine in 2014.

The current resolute and strong reaction of the West to Russian aggression can be understood only if we bear in mind almost a decade of weak Western responses to the Putin regime’s increasing confidence and aggressiveness. Now there is more understanding that Putin will not stop and that he is becoming a direct and real threat to Western security architecture and to European peace.

It is because of this threat that the West is now helping Ukraine. The West appreciates that Ukraine is a democratic country and is genuinely trying to undertake anti-corruption and other reforms, but that isn’t why the West is providing military aid to Ukraine. The West is imposing tough and broad sanctions on Russia and is providing military aid to Ukraine because Western policymakers and security planners feel that Russia’s aggression towards Ukraine is a direct attack on Europe’s security architecture.

It is very different when it comes to Myanmar. Min Aung Hlaing’s coup and the Tatmadaw’s war of terror against the people of Myanmar are seen in very negative terms among Western policymakers. But they do not see any of the fundamental security interests of the West being directly under threat and under attack in Myanmar.

The West is also reluctant to provide more resolute assistance to the Myanmar resistance movement, particularly any sort of military resistance, because all of Myanmar’s neighbours and other regional players are against that. The West is particularly concerned that if it starts to arm the anti-junta movement, that will probably immediately lead to China standing openly and fully behind the military junta. The US does not want to make Myanmar a battleground of a proxy war between the West and China, because US policymakers and security strategists are aware that such a proxy war would bring no good to the people of Myanmar, and it is almost certain that a junta backed by China would prevail over an anti-junta resistance movement backed by the West.

China is too close, too big, and too powerful, and it has much greater national interests at stake in Myanmar than the US or UK have in the country. The EU has no national interests in Myanmar at all and will never take any risk in the country.

Myanmar is too far away. There is no such broad public demand for “something to be done”

Another reason for the stronger response to the Ukrainian crisis is that many in Europe feel strong sympathy and solidarity with Ukrainians. Russia is a big factor in European history. The Russian and Soviet shadow falling upon Europe is long. Many current members of the European Union—the Baltic states (Lithuania, Estonia and Latvia) as well as Central European and East European states (Poland, Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, Romania, Bulgaria)—have all been occupied by the Russian army and have been either part of the Soviet Union (Baltic states) or for decades forcefully kept in the Warsaw Pact. For that reason, broad segments of European citizenry are very sensitive to any aggressive Moscow policies. Western governments can be strong and tough, because they see that many in Europe are in full solidarity with Ukrainians.

Myanmar is too far away. There is no such broad public demand for “something to be done”.

I think it is right that the NUG has expressed support for Ukrainians, while the junta is among the few rogue regimes around the world that have expressed support for Putin. It is also very good that the Myanmar protest movement, activists and citizens are in different ways expressing support for Ukrainians.

But it is wishful thinking to hope that the resolute response of the West to Russian aggression in Ukraine will bring quick and significant change in the Western approach toward Myanmar. I would like to see the West recognise the NUG, and I would like someone to provide several dozen Man-Portable Air-Defence Systems (MANPADS) and several hundred Man-Portable Anti-Tank Guided Missiles (MPATGM), because I believe that would significantly undermine the Tatmadaw’s capacity to terrorise the civilian population and bring us closer to the fall of the junta. But a lot still needs to be done to achieve that.

The most important would be to have much broader political unity behind the NUG and the National Unity Consultative Council than we have now and to have much more active military cooperation of different armed stakeholders.

I believe that it is important to always have in mind that the international factor will have about a 20% influence on the final outcome in Myanmar, while 80% will be domestically decided. Myanmar’s neighbours and other regional and international actors do not really want to get too involved. They see it as too complex. That is why they prefer to do what they have been doing so far—containing the Myanmar crisis to keep it from spreading over the country’s borders and just sitting and waiting until the conflict exhausts itself internally.

Ukraine has also invited foreigners to join them in defending their country. Should the NUG adopt the same tactic?

It is true that Ukraine has opened the possibility of foreigners coming to help them in their defence, and some Western countries are quickly giving legal approval for their citizens to join Ukrainian defence forces. But it would be very wrong to overestimate the importance of this factor.

What is really important is that Ukraine is already eight years into a de facto war with Russia in East Ukraine. Since the initial Russian occupation of Crimea and Donetsk and Luhansk in 2014, Ukraine has been in a low-intensity self-defence war with Russia. There are about half a million Ukrainian citizens who have spent some time on the frontline in East Ukraine. That means they have military training, frontline experience and huge motivation to defend their country.

Another thing is that Ukrainian society has fully unified in the face of Russian aggression. Not only were Ukrainian army and reserve units immediately mobilised, but huge numbers of ordinary citizens, both men and women, also volunteered to join territorial defence structures. There are a lot Ukrainians who work abroad. In the last seven days, 66,000 of them have returned to the country to join defence units. So while more than one million women and children are escaping to safety in European countries, tens of thousands of Ukrainian men are going back to fight.

This is what is really important: the willingness of Ukrainians to fight and defend their country—readiness to take the ultimate risk, to sacrifice life if necessary, not to let Putin and Russia occupy Ukraine. Putin has publicly said that Ukrainians do not exist as a nation and that Ukraine does not have the right to exist as a state. Ukrainians are ready to fight to prove that they are a nation and that they have their own independent state.

And it is not only about readiness to fight with weapons. Ukraine is not defending itself only with armed resistance. It is also fighting with civic resistance. Hundreds of thousands of volunteers have self-organised to help with humanitarian aid, to assist those who are escaping from bombed cities or to fulfil other necessary tasks. Many talented and creative Ukrainians are fully involved in information and psychological war and Ukrainians are already now fully winning that war.

It is wrong to believe that foreign volunteers are any significant factor in the Ukrainian self-defence. There are some, relatively small numbers, of foreign volunteers who have previous military experience that might bring some useful military skills, particularly with weapons that have been recently provided by Western countries to Ukraine. But still, it is not foreign volunteers that will fight and decide the war in Ukraine. It is Ukrainians themselves.

Compared with Ukraine’s response to the Russian invasion, Myanmar’s spring revolution seems unsatisfactory.

There is nothing satisfying in the current Russian war of aggression against Ukraine. True, Ukrainian defence is heroic and they will probably succeed in defending their country. But the price is and will be huge. Already, 1.5 million refugees have left Ukraine, and there will be more. What is happening right now is one of the quickest human exoduses in history. Numerous cities have already been severely damaged, and much more destruction is expected. And we can’t rule out the possibility that Putin may even use nuclear weapons.

What impact, if any, do you think the war in Ukraine will have on countries like Myanmar?

If the West succeeds in significantly weakening Putin’s capacity to wage a war of occupation against Ukraine through broad and tough sanctions, and if the current wave of disinvestment and withdrawal of Western multinational companies from Russia weakens the Russian economy and creates social uprisings within Russia, and if Ukrainians manage to inflict significant losses on the occupying Russian army, then dictators around the world, including Min Aung Hlaing, will be weakened as well.

Putin and Russia have in the last 10-15 years been reliable and aggressive supporters of many dictatorial regimes around the world. Russia will no longer be able to play that role. In a number of countries where the democratic aspirations of citizens have been brutally suppressed by local regimes supported by Putin, democracy drives will be reactivated.

However, these global changes will be slow to fully develop and will be slow to have an impact on Myanmar. Do not forget that the war in Ukraine and Western response has just started. We still do not know how long it will last or what the final outcome and consequences will be.

What other lessons can we in Myanmar learn from the Russia-Ukraine conflict?

The biggest lesson is, I think, that Ukrainians are fully united around the idea of their national identity and around the idea of their independence and freedom. In Myanmar, we have many brave citizens and a number of the country’s political, armed and civic stakeholders who are also united behind the idea of federal democracy and who want once and forever to liberate the country and the people from repressive and predatory military rule. But we also have many other stakeholders who are sitting on the fence.

Instead of comparing the Ukrainian government and the NUG, it would be better to compare the solidarity of European neighbours toward Ukraine and the cynical and hypocritical lack of solidarity among Myanmar’s neighbours

Some others are using the current crisis to try to advance their own interests. They do not want to be part of a bad unity under military rule, but they don’t want to be part of any other unity, even a federal one, either. And there are also stakeholders who prefer a never-ending, no-war-no-peace situation because that is the best environment for their illegal business interests.

What do you think of the NUG’s policies or defence strategies? What changes should it make?

It’s not fair to compare what the Ukrainian government can achieve and what the NUG can achieve at this moment. The Ukrainian government and the NUG are, first of all, operating in very different geopolitical contexts. Ukrainian European neighbours are ready to provide significant support to the Ukrainian government. Myanmar’s neighbours—Thailand, China and India—are not even ready to open humanitarian corridors to those whose villages and cities have been burned and bombed. So, instead of comparing the Ukrainian government and the NUG, it would be better to compare the solidarity of European neighbours toward Ukraine and the cynical and hypocritical lack of solidarity among Myanmar’s neighbours.

The Ukrainian government controls a significant part of the country’s territory and almost the whole population. It is a government that has its own army and runs the state. The state is under attack by foreign enemies, but it is still the state. The NUG has none of that. And yet, Myanmar’s resistance to the junta and the Tatmadaw has achieved a lot. It is not just the NUG that has played a role. Many others have also made their own contributions. But the NUG has played and is still playing an extremely important role.

Instead of undermining trust in the NUG, what I think will be good to do is to get inspiration from the heroism of Ukrainians, understand that the heroism of the people of Myanmar has been as impressive as the heroism of Ukrainians, and remobilise and reunite different forces—political, armed and civic ones—in a common struggle against Min Aung Hlaing and his regime for a future federal, democratic and socio-economically just Myanmar.

Citizens of Ukraine still have a heavy and hard struggle ahead of them to defend their country and to achieve their freedom. The citizens of Myanmar also have a heavy and hard struggle ahead of them to prevail over the junta, to liberate themselves from the military, and to build a federal and democratic country. Both can achieve their goals, and I believe they will achieve them.