Myanmar was forecast to earn 2,305 billion kyat (now about US$1.4 billion) from oil and gas in the year to March 2022, according to a Myanmar budget document drawn up before the coup.

This would be just over 10% of total government revenues this year – slightly lower than in previous years.

It is not certain whether Myanmar will actually earn its forecasted 2,305 billion kyat because oil and gas prices are volatile and change frequently.

Where does this revenue come from?

By far the biggest proportion of extractive industry revenue in Myanmar comes from four big offshore projects producing natural gas.

The Yadana project is operated by France’s Total, which produces and transports the gas as well as owning 32.14% of the project. The other investors are Chevron of the US, a unit of Thailand’s PTT and a 15% stake held by Myanma State Oil and Gas Enterprise (MOGE), which is owned by Myanmar. Most of the gas is piped to Thailand and bought by PTT while some is supplied to Myanmar’s domestic market.

The Shwe project is operated by Korea’s POSCO and exports gas to China via a pipeline. The other investors in the project are owned by foreign governments: Korea’s KOGAS, MOGE and the Indian companies ONGC Videsh and GAIL. China’s China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC) is an investor in the pipeline

The Yetagun project is operated by Petronas, the state oil company of Malaysia, and its co-investors are MOGE, a subsidiary of PTT and Nippon Oil, whose ultimate owners include the government of Japan. Petronas suspended operations in April 2021 for technical rather than political reasons.

The Zawtika project is operated and mostly owned by a subsidiary of Thailand’s PTT, with MOGE holding a 20% stake. The gas is mostly piped to Thailand.

Another pipeline from Myanmar to China is jointly owned by CNPC and MOGE and used to ship crude oil rather than natural gas.

What form do gas revenue payments take?

Myanmar receives several types of gas revenue, including the government’s share of profits from gas export sales, royalties (a fee based on gas volumes) and income tax on the profits of oil companies.

As well as collecting gas sales profits and royalties for the government, MOGE earns its own profits from its shareholdings in various gas fields and pipelines. To make things even more complicated, MOGE and other oil companies pay transit fees to use the pipelines, which they also own.

Despite all these distinctions, the reality is that all gas revenues are in the hands of the military junta because it controls MOGE, the Finance Ministry and state-owned banks.

So when foreign companies say that they don’t deal with the generals, this distinction may be true on paper but is arguably meaningless in reality.

So what did Total and Chevron just do?

Total and Chevron announced last week that dividend payments from the Yadana pipeline to all its owners would be suspended, which means that MOGE (which owns 15 per cent of the pipeline) could lose around US$40 million a year in profits.

The two giant energy companies appear to have been prompted by criticism of their dealings with the military junta. The decision is symbolically important because it suggests that oil companies can cut off payments to the military junta if they really want to.

Experts note that these pipeline dividends are only a small part of the revenues that the military junta gets from Yadana.

What’s more, dividends are usually paid at the end of a financial year, which in Myanmar’s case is March 2022, so the suspension may not have an immediate effect on the junta’s finances.

To put serious pressure on the junta’s finances, Total and other foreign oil companies would have to stop all the revenue flows to Myanmar state institutions and channel the money into accounts which the junta cannot access. This is what the opposition wants.

Total says that cutting off the money would breach its contract with Myanmar. However, international sanctions could override Myanmar law and oblige oil companies to do this.

Where exactly does all the gas revenue go?

It isn’t possible to know for sure. Since the coup, Myanmar has been suspended from the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI), which tracked the flow of revenues from oil and gas companies to the government, and the companies themselves are saying relatively little.

It is known how the system used to work for the Yadana project: a 1995 agreement between Total and Myanmar shows that PTT would buy the gas and make payment into a bank outside Myanmar. Total, as the operator of the project, would then instruct that bank to divide up that money between the Myanmar government and the investors in Yadana, according to the contracts between them, and transfer the money to their bank accounts.

It is likely that Yadana and other gas projects still use a system like this.

Korea’s POSCO has said that Myanmar’s revenues from the Shwe project are paid into an account held by Myanma Foreign Trade Bank (MFTB) with Singapore’s Overseas Chinese Banking Corporation. Total says Myanmar’s revenues from Yadana are paid in Thailand. This may mean an MFTB account at a Thai bank, though Total has not said this.

It is a serious problem that gas revenue is paid into foreign bank accounts because the military junta, which controls MFTB, could order the bank to move the money to places where it cannot easily be traced, such as front companies in tax havens. This would make it easier for the generals to evade international sanctions, to secretly buy weapons or simply to steal money and keep it for themselves.

Why is it all so complicated?

The gas revenue payments are set out in hundreds of pages of legal agreements between the oil companies and the government.

This complexity is common in the oil industry but it has often been exploited by oil companies to extract more profit from poorer countries.

This is why it is questionable that the profit margin on the Yadana gas pipeline is an extremely high 97% before tax, because high pipeline profits seem to benefit the foreign oil companies at Myanmar’s expense.

Total says the profits of the Yadana pipeline and gas fields, taken together, are not unusually high. This claim is impossible to check because Total has not published the necessary data.

The complexity of the oil industry is also a problem because in many countries it has obscured corrupt transactions between oil companies and government officials.

There is no evidence or suggestion that energy companies active in Myanmar have facilitated corrupt payments.

However, it is still common for oil companies to pay taxes and other revenues to governments in countries where corruption is a big problem, despite knowing that some of this public money will be stolen.

What will happen now?

Unless foreign oil companies decide to cut off the flow of gas revenues to the military junta, or are forced to do so by international sanctions, those revenues will continue to prop up the junta and are vulnerable to being stolen by corrupt officials.

This is a Myanmar Now news story in association with Finance Uncovered

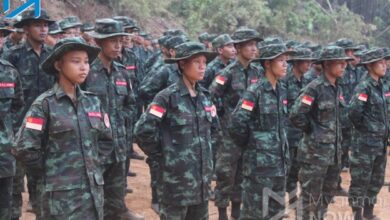

![Resistance fighters holding heavy weapons ammunition in central Myanmar. (Photo: Freedom Revolution Force [FRF])](https://myanmar-now.org/en/wp-content/uploads/sites/5/2024/04/438869056_443267851680128_1706386881626943924_n-390x220.jpeg)