Content warning: This article contains pictures and detailed descriptions of killings, which may be upsetting to some readers.

The time was one o’clock in the morning of March 1, 2023.

Kan Kaung and two friends were asleep in a hut at a farm a few miles from Tar Taing, a village located at the western edge of Sagaing Township, when a group of men in sports pants and regular shirts, but also wearing bullet-proof vests, shook them awake. Kan Kaung, who is in his 20s, felt a chill run up his spine as realised that the men, who were pointing guns directly at them, were Myanmar army soldiers.

There were around 70 of them. They told Kan Kaung and his friends to come with them and made them carry their supply backpacks. Before they knew it, the three young men were marching alongside the junta column near the confluence of the Ayeyarwady and Muu rivers, with only the lights on their mobile phones to help them see their way in the dark.

They didn’t know where they were going, but they could hear some of the soldiers talking indistinctly about their target. “Which one is Kyaw Zaw?” they said, apparently trying to identify someone in a photo.

After around four hours, the soldiers stopped to take a rest. Some slept, but Kan Kaung and the other captives were too terrified to close their eyes. They just held the backpacks tight as they watched and waited. Sitting there tensely, they could also smell alcohol. Finally, after about an hour, they carried on with their journey.

It was just before dawn when they reached Tar Taing. The column then split up into groups of 10. Their leader ordered them not to open fire: “Arrest everyone,” he said. Meanwhile, Kan Kaung and his friends were taken to a house at the western edge of the village by a group of eight soldiers who warned them that they would be killed if they attempted to flee.

Tar Taing is a small village of around 80 households. But before the day was over, it would be the scene of one of the worst massacres carried out by Myanmar’s military since it seized power two years ago. By the time Kan Kaung and his fellow captives were taken away, a total of 17 people, including the resistance leader Kyaw Zaw that the soldiers had been talking about, would be dead—killed and dismembered by the monstrous “Ogre Column” that had been sent to terrorise local residents and resistance fighters alike into submission.

The victims, who included three women, ranged in age from 17 to 67. When their bodies were recovered the day after they were killed, many were found to have bullet wounds to the back of their heads. Pro-junta propaganda outlets claimed they were all “terrorists” opposed to the regime, but Myanmar Now’s investigations have indicated that 47-year-old Kyaw Zaw, who was subjected to the most gruesome treatment, was the only non-civilian among them.

A new level of savagery

Two years after overthrowing Myanmar’s elected civilian government, the country’s military has escalated its terror tactics against its opponents and those who support them. In February, it declared martial law in 14 Sagaing townships, although not the one with the region’s namesake, where Tar Taing is located, nor Myinmu, just a few miles away. Still, since then, in these townships it has engaged in some of its worst atrocities, sowing not only death and destruction, but also making a display of its savagery by sharing photos of corpses desecrated by its troops in the most hideous fashion.

In Tar Taing, the Ogre Column didn’t simply force its way in and start torching houses and killing villagers unable to flee; it crept up on its inhabitants, captured them, and then murdered them at will. And when that was done, it turned the bodies into photographic trophies to instil terror in a public already appalled by the military’s cruelty. A day after the massacre in Tar Taing, Myanmar Now spoke to Kan Kaung and four residents of the village who witnessed this barbaric behaviour first-hand. All names have been changed for their protection.

A butchered body

From the house where he was being held, Kan Kaung could easily hear the screams and cries coming from the monastery on the opposite side of the village. But he also saw some of those who would later be killed, including a woman in her late 30s or early 40s and an elderly man who were both brought into the house. The woman had her hands tied behind her back and had been accused of having a gun in her house.

The entire village was filled with the sound of soldiers shouting threats at those they had captured, but no shots were fired for the first three hours after the raid began. Then a shootout with local resistance forces started. This clash lasted about half an hour and included the eight soldiers who were guarding the house. Kan Kaung remained perfectly still the whole time, mindful of the soldiers’ threat to kill him if he tried to escape.

After the fighting stopped, another soldier entered the house and showed a photo of a man with multiple gunshot wounds to the two Tar Taing villagers, demanding to know if the man was Kyaw Zaw. After looking at the soldier’s phone, the villagers confirmed that the victim was, in fact, Kyaw Zaw. After receiving the answer he wanted, the soldier went to get a meat cleaver and left the house again.

When he returned about half an hour later, the soldier no longer had the cleaver. But he had a new photo on his phone that he insisted on pushing into the faces of the two captured villagers.

“He showed his phone to the villagers and told them that this is what happened to Kyaw Zaw. He also told them to take notes,” Kan Kaung told Myanmar Now.

The soldier asked Kan Kaung if he wanted to see the photo, too, but he said he didn’t dare look at it. The photo, as he later learned, showed Kyaw Zaw’s body, not just dead, but also decapitated, dismembered and eviscerated.

Murder in the monastery

U Moe, a Tar Taing resident in his 60s, was among the 100 or so villagers who were held in the village’s monastery throughout the nearly 24-hour ordeal. Soon after he was captured, he and around 10 other elderly villagers were taken to the monastery’s main building, while some others who had their hands tied behind their backs were forced to lie face down on the ground in the monastery compound.

“The soldiers called themselves the ‘Ogre Column.’ They said they weren’t going to torch the village, but were just looking for PDFs,” he said, referring to members of the anti-regime People’s Defence Force.

According to U Moe, the soldiers had a list of names on their phones that they used to separate the villagers into different groups. Around 80 people who were not on the list filled the building that he was in, which housed the monastery’s altar and Buddha images. This group was further divided by gender, with the men staying upstairs and the women downstairs, he said.

The ones lying on the ground outside were all people whose names were on the list. They were also joined by a few villagers accused of trying to escape or of talking back to the soldiers.

The soldiers called themselves the ‘Ogre Column.’ They said they weren’t going to torch the village, but were just looking for PDFs

Although the windows and doors of the monastery’s main building were all closed, U Moe said he could clearly hear what was happening outside. The soldiers were beating the captives they had tied up, who were crying out in agony. Occasionally, this sound would be punctuated by that of a gunshot.

This continued until around 5pm, he said. That was when some of the soldiers came back into the building to get a few of the women, who were told to start cooking dinner for them and the other prisoners. (On the other side of the village, Kan Kaung said he saw soldiers catching chickens for the women to cook. They also stole dried beef from the villagers’ homes, he added.)

After eating, the soldiers settled in for the night. A few were assigned to guard duty, occasionally firing their guns out into the darkness whenever the resistance sources shot at them to remind them that they were still there.

A trail of bodies

The next morning, the Ogre Column set off in the direction of Nyaung Yin, a village about 4km west of Tar Taing. The column was divided into four groups this time, each one accompanied by a number of hostages. The first group left at around 7am, but the third group, which included Kan Kaung and his friends and five other men, didn’t leave until 8am.

Before reaching Nyaung Yin, Kan Kaung and his friends were separated from the other five, who stayed behind with five soldiers. As he was being led away, Kan Kaung said he heard at least eight gunshots being fired behind him.

“We were scared out of our minds, even though they said they weren’t going to kill us. I asked one of the soldiers what was going to happen to us, and he said that only those who had been tied up would be killed,” Kan Kaung told Myanmar Now.

Later he saw the bodies of other victims—villagers who had gone ahead of them with the first and second groups.

“There were five bodies in one place, and three more somewhere else. Some were on their stomachs, some on their backs. Some had been shot in the head from the behind while kneeling down,” he said.

When they reached Nyaung Yin, they found that its inhabitants had already fled. The soldiers they were with took over the first abandoned house they approached on the eastern edge of the village. And it was at this point that Kan Kaung and his friends were finally released with a final warning: Don’t try anything.

‘I can’t even describe it’

Others who saw the bodies claimed that the victims were not merely murdered, but also tortured and sexually assaulted.

“They were beaten so badly before they were killed that their skulls had caved in. It was so hard to look at. The female victims also appeared to have been sexually assaulted before they were killed,” said a local who was part of the group that retrieved the bodies on March 2.

Ko Kyaw, a member of a local defence team who also helped to collect the bodies, said the underwear of the female victims had been torn and that onions had been forced into their vaginas. Myanmar Now was unable to verify this information.

Despite the brutal treatment they were subjected to, it appeared that almost none of those who had been killed were members of the armed resistance. Most were farmers or fishermen, and a few were from other villages. One, a 35-year-old resident of the neighbouring village of Shwe Hlay named Chit Kaung, was allegedly captured near Tar Taing while trying to find a missing cow.

Many of the victims were related. Ko Thein, a 25-year-old Tar Taing native, lost his mother, brother, brother-in-law and aunt that day. He survived only because he was not in Tar Taing when the soldiers arrived.

“They killed my family members in such an unimaginable way. I can’t even describe it,” he said.

Two more bodies were later discovered north and south of Tar Taing. One, belonging to a 25-year-old man named Yarhu, was found south of the village on the bank of the Ayeyarwady River. Like Kyaw Zaw, the only confirmed member of the resistance among all the victims, Yarhu’s body was decapitated and dismembered.

“It looked like they put his neck on some kind of chopping block,” said one local who saw the body.

Terrorist actions

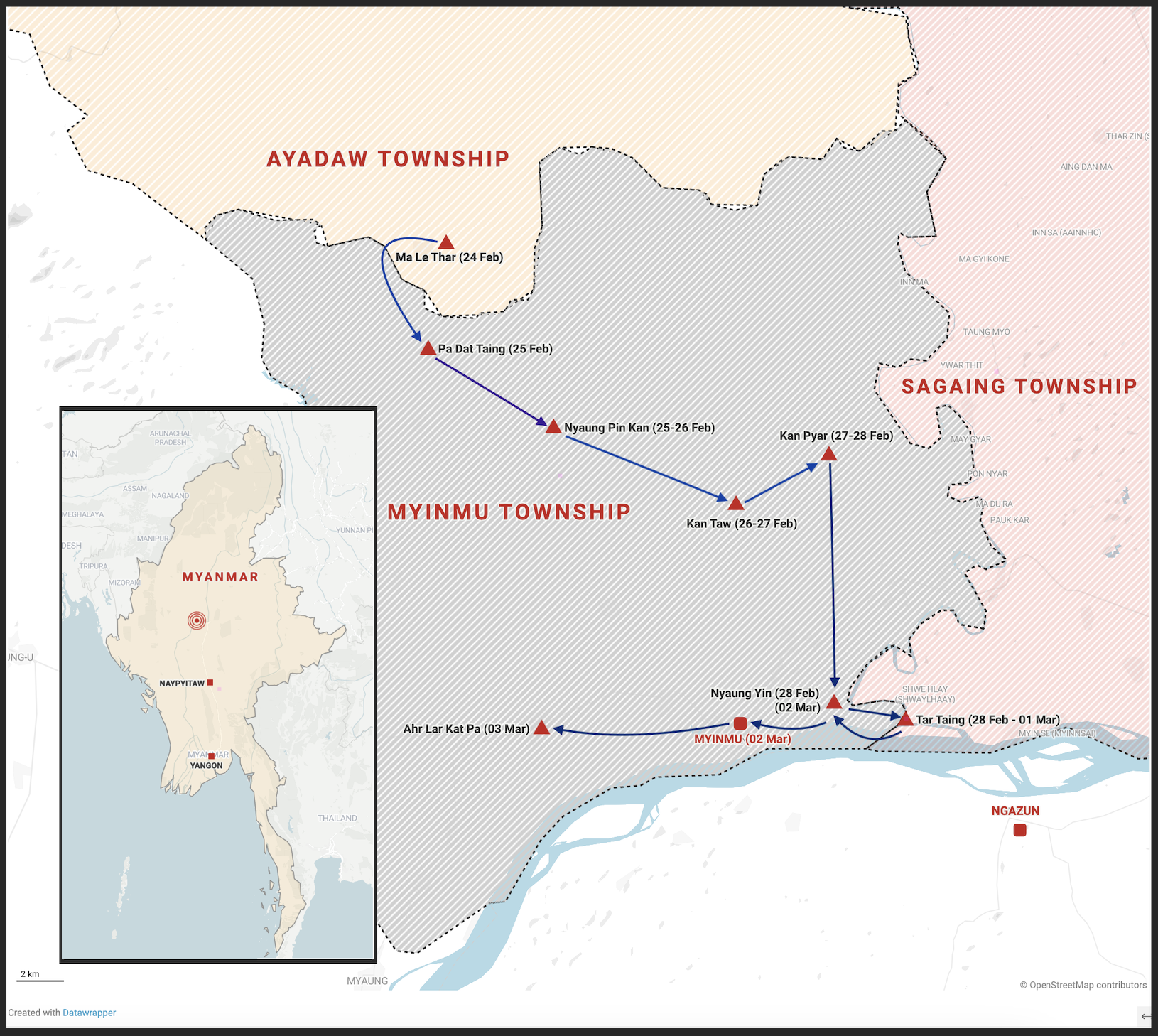

The self-described Ogre Column was, in fact, a group of nearly 70 soldiers that had been transported to the village of Ma Lal Thar in Ayadaw Township, some 50km north of Tar Taing, on February 24.

The same column also raided at least 10 villages in Myinmu and Sagaing townships. A total of 23 locals were killed in just one week and seven of them, including five in the village of Pa Dat Taing and two in Tar Taing, were decapitated and dismembered.

Moe Gyo, the leader of the Sagaing-based Sartaung Moe Gyo People’s Defence Team, encountered the Ogre Column in Kandaw, a village in Myinmu Township. Those same soldiers beheaded two members of his group after capturing them.

“They are taunting us and trying to instil fear in us. That is exactly why we can’t forgive them,” he said.

On March 6, the publicly mandated National Unity Government (NUG) held a press conference highlighting the Tar Taing massacre. Aung Myo Min, the NUG’s human rights minister, said that junta forces have committed at least 32 massacres over the past two years.

“We have proved multiple times how cruel the military is,” he said, addressing the international community. “I have urged you before and I am urging you again. Please stop the military council’s terrorist actions as soon as possible.”